United States presidential line of succession

| Part of a series on Orders of succession |

| Presidencies |

|---|

The United States presidential line of succession is the order in which the vice president of the United States and other officers of the United States federal government assume the powers and duties of the U.S. presidency (or the office itself, in the instance of succession by the vice president) upon an elected president's death, resignation, removal from office, or incapacity.

The order of succession specifies that the office passes to the vice president; if the vice presidency is simultaneously vacant, the powers and duties of the presidency pass to the speaker of the House of Representatives, president pro tempore of the Senate, and then Cabinet secretaries, depending on eligibility.

Presidential succession is referred to multiple times in the U.S. Constitution: Article II, Section 1, Clause 6, the 12th Amendment, 20th Amendment, and 25th Amendment. The vice president is designated as first in the presidential line of succession by the Article II succession clause, which also authorizes Congress to provide for a line of succession beyond the vice president. It has done so on three occasions. The Presidential Succession Act was adopted in 1947, and last revised in 2006. The 25th Amendment, adopted in 1967, also establishes procedures for filling an intra-term vacancy in the office of the vice president.

The Presidential Succession Act refers specifically to officers beyond the vice president acting as president rather than becoming president when filling a vacancy. The Cabinet has 15 members, of which the secretary of state is highest and fourth in line (after the Senate president pro tem); the other Cabinet secretaries follow in the order of when their departments (or the department of which their department is the successor) were created. Those heads of department who are constitutionally not "eligible to the Office of President" are disqualified from assuming the powers and duties of the president through succession and skipped to the next in line. Since 1789, the vice president has succeeded to the presidency intra-term on nine occasions: eight times due to the incumbent's death, and once due to resignation. No one lower in the line of succession has ever been called upon to act as president.

Widely considered a settled issue during the late 20th century, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 demonstrated the potential for a decapitation strike that would kill or incapacitate multiple individuals in the presidential line of succession in addition to many members of Congress and the federal judiciary. In the years immediately following the attacks, numerous wide-ranging discussions were started, in Congress, among academics and within the public policy community about continuity of government concerns including the existing constitutional and statutory provisions governing presidential succession. These discussions remain ongoing. One effort put forward by the Continuity of Government Commission, a nonpartisan think tank, produced three reports (2003, 2009, and 2011), the second of which focused on the implicit ambiguities and limitations in the succession act, and contained recommendations for amending the laws for succession to the presidency.

Current order of succession

The presidential order of succession is set by the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, as amended.[1] The order consists of congressional officers, followed by the members of the cabinet in the order of the establishment of each department, provided that each officer satisfies the constitutional requirements for serving as president.[2] In the table below, the absence of a number in the first column indicates that the office is either vacant, or that the incumbent is ineligible.

Constitutional provisions

Presidential eligibility

Article II, Section 1, Clause 5 of the Constitution sets three qualifications for holding the presidency: One must be a natural-born citizen of the United States (or a citizen at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, in 1788), be at least 35 years of age and have been a resident in the United States for at least fourteen years.[5][C]

Presidential succession

The presidential line of succession is mentioned in four places in the Constitution:

- Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 makes the vice president first in the line of succession and allows the Congress to provide by law for cases in which neither the president nor vice president can serve.[7]

- The 12th Amendment provided that the vice president would also fill any vacancy of the presidency arising from failure of the House of Representatives to choose a president in a contingent election.[8]

- The 20th Amendment, Section 3, supersedes the above 12th Amendment provision, by declaring that if the president-elect dies before his term begins, the vice president-elect becomes president on Inauguration Day and serves for the full term to which the president-elect was elected, and also that, if on Inauguration Day, a president has not been chosen or the president-elect does not qualify for the presidency, the vice president-elect acts as president until a president is chosen or the president-elect qualifies. It also authorizes Congress to provide for instances in which neither a president-elect nor a vice president-elect have qualified.[9]

- The 25th Amendment, Section 1, clarifies Article II, Section 1, Clause 6, by stating unequivocally that the vice president is the direct successor of the president, and becomes president if the incumbent dies, resigns or is removed from office. It also, in sections 3 and 4, provides for situations where the president is temporarily disabled, such as if the president has a surgical procedure or becomes mentally unfit, establishing procedures whereby the vice president can become acting president. Additionally, in Section 2, the amendment provides a mechanism for intra-term vice presidential succession, establishing that a vice presidential vacancy will be filled by a president's nominee upon confirmation by a majority vote of both houses of Congress.[D] Previously, whenever a vice president had succeeded to the presidency or had died or resigned from office, the vice presidency remained vacant until the next presidential and vice presidential terms began; there were 16 such vacancies prior to 1967.[11]

Succession acts

Act of 1792

The Presidential Succession Act of 1792 (Full text ![]() ) provided for succession after the president and vice president: first, the president pro tempore of the Senate, followed by the speaker of the House.[12] The statute provided that the presidential successor would serve in an acting capacity, holding office only until a new president could be elected.[13] A special election was to be held in November of the year in which dual vacancies occurred (unless the vacancies occurred after the first Wednesday in October, in which case the election would occur the following year; or unless the vacancies occurred within the last year of the presidential term, in which case the next election would take place as regularly scheduled). The persons elected president and vice president in such a special election would have served a full four-year term beginning on March 4 of the next year. No such election ever took place.[14]

) provided for succession after the president and vice president: first, the president pro tempore of the Senate, followed by the speaker of the House.[12] The statute provided that the presidential successor would serve in an acting capacity, holding office only until a new president could be elected.[13] A special election was to be held in November of the year in which dual vacancies occurred (unless the vacancies occurred after the first Wednesday in October, in which case the election would occur the following year; or unless the vacancies occurred within the last year of the presidential term, in which case the next election would take place as regularly scheduled). The persons elected president and vice president in such a special election would have served a full four-year term beginning on March 4 of the next year. No such election ever took place.[14]

Various framers of the Constitution, such as James Madison, criticized the arrangement as being contrary to their intent. The decision to build the line of succession around those two officials was made after a long and contentious debate. In addition to the president pro tempore and the speaker, both the secretary of state and the chief justice of the Supreme Court were also suggested.[14] Including the secretary of state was unacceptable to most Federalists, who did not want the then secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson, who had become the leader of the opposition Democratic-Republicans, to follow the vice president in the succession, and many objected to including the chief justice due to separation of powers concerns.[7][15]

Act of 1886

The Presidential Succession Act of 1886 (Full text ![]() ) established succession to include the members of the President's cabinet in the order of the establishment of the various departments, beginning with the Secretary of State,[E] and stipulated that any official discharging the powers and duties of the presidency must possess the constitutional qualifications to hold the office.[13] The president pro tempore and Speaker were excluded from the new line, and the provision mandating a special presidential election when a double vacancy arose was also dropped.[14]

) established succession to include the members of the President's cabinet in the order of the establishment of the various departments, beginning with the Secretary of State,[E] and stipulated that any official discharging the powers and duties of the presidency must possess the constitutional qualifications to hold the office.[13] The president pro tempore and Speaker were excluded from the new line, and the provision mandating a special presidential election when a double vacancy arose was also dropped.[14]

The need for increasing the number of presidential successors was abundantly clear to Congress, for twice within the span of just over four years it happened that there was no one in the presidential line of succession. In September 1881, when Chester A. Arthur succeeded to the presidency following James A. Garfield's death, there was no vice president, no president pro tempore of the Senate, and no Speaker of the House of Representatives.[8] Then, in November 1885, Grover Cleveland faced a similar situation, following the death of Vice President Thomas A. Hendricks, as the Senate and the House had not convened yet to elect new officers.[16]

Act of 1947

The Presidential Succession Act of 1947 (Full text ![]() ), which was signed into law on July 18, 1947,[13] restored the speaker of the House and president pro tempore of the Senate to the line of succession—but in reverse-order from their 1792 positions—and placed them ahead of the members of the Cabinet, positioned, as before, in the order of the establishment of their department.[3][F]

), which was signed into law on July 18, 1947,[13] restored the speaker of the House and president pro tempore of the Senate to the line of succession—but in reverse-order from their 1792 positions—and placed them ahead of the members of the Cabinet, positioned, as before, in the order of the establishment of their department.[3][F]

Placing the speaker and the president pro tempore (both elected officials) back in the succession and placing them ahead of cabinet members (all of whom are appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate), was Harry S. Truman's idea. Personally conveyed to Congress in June 1945, two months after becoming president upon Franklin D. Roosevelt's death, the proposal reflected Truman's belief that the president should not have the power to appoint to office "the person who would be my immediate successor in the event of my own death or inability to act", and that the presidency should, whenever possible, "be filled by an elective officer."[13][17]

Further amendments

The 1947 act has been modified several times, with changes being made as the face of the federal bureaucracy has changed over the ensuing years. Its most recent change came about in 2006, when the USA PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorization Act added the secretary of homeland security to the presidential line of succession.[18][G]

Ambiguities regarding succession and inability

Although the Presidential Succession Clause in Article II of the Constitution clearly provided for the vice president to take over the "powers and duties" of the presidency in the event of a president's removal, death, resignation, or inability, left unclear was whether the vice president became president of the United States or simply temporarily acted as president in a case of succession.[7] Some historians, including Edward Corwin and John D. Feerick,[20] have argued that the framers' intention was that the vice president would remain vice president while executing the powers and duties of the presidency until a new president could be elected.[21]

The hypothetical debate about whether the office or merely the powers of the office devolve upon a vice president who succeeds to the presidency between elections became an urgent constitutional issue in 1841, when President William Henry Harrison died in office. Vice President John Tyler claimed a constitutional mandate to carry out the full powers and duties of the presidency, asserting he was the president and not merely a temporary acting president, by taking the presidential oath of office.[22]

Many around him—including John Quincy Adams,[20][23] Henry Clay[24] and other members of Congress,[23][24] along with Whig party leaders,[24] and even Tyler's own cabinet[23][24]—believed that he was only acting as president and did not have the office itself. He was nicknamed "His Accidency" and excoriated as a usurper.[22] Nonetheless, Tyler adhered to his position, even returning, unopened, mail addressed to the "Acting President of the United States" sent by his detractors.[25] Tyler's view ultimately prevailed when the House and Senate voted to accept the title "President",[24] setting a precedent for an orderly transfer of presidential power following a president's death,[22] one that was subsequently written into the Constitution as section 1 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment.[21]

Even after the precedent regarding presidential succession due to the president's death was set, the part of the Presidential Succession Clause that provided for replacing a disabled president remained unclear. What constituted an "inability"? Who determined the existence of an inability? Did a vice president become president for the rest of the presidential term in the case of an inability; or was the vice president merely "acting as President"? Due to this lack of clarity, later vice presidents were hesitant to assert any role in cases of presidential inability.[26] Two situations are noteworthy:

- On July 2, 1881, President James A. Garfield was shot; hit from behind by two bullets (one grazing his arm and the other lodging in his back).[27] The president wavered between life and death for 80 days after the shooting; it was the first time that the nation as a whole experienced the uncertainties associated with a prolonged period of presidential inability.[8] Most disconcerting, especially for Garfield administration personnel and members of Congress, was the lack of constitutional guidance on how to handle the situation. No one was sure who, if anyone, should exercise presidential authority while the president was disabled; many urged Vice President Chester A. Arthur to step up, but he declined, fearful of being labeled a usurper. Aware that he was in a delicate position and that his every action was placed under scrutiny, Arthur remained secluded in his New York City home for most of the summer. Members of the Garfield Cabinet conferred daily with the president's doctors and kept the vice president informed of significant developments on the president's condition.[27]

- In October 1919, President Woodrow Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke. Nearly blind and partially paralyzed, he spent the final 17 months of his presidency sequestered in the White House.[28] Vice President Thomas R. Marshall, the cabinet, and the nation were kept in the dark over the severity of the president's illness for several months. Marshall was pointedly afraid to ask about Wilson's health, or to preside over cabinet meetings, fearful that he would be accused of "longing for his place". Though members of both parties in Congress pledged to support him if he asserted his claim to the presidential powers and duties, Marshall declined to act, or to do anything that might seem ambitious or disloyal to Wilson.[29] At a time when the fight over joining the League of Nations was reaching a climax, and domestic issues such as strikes, unemployment, inflation and the threat of Communism were demanding action, the operations of the executive branch were once more hampered due to the fact that there was no constitutional basis for declaring that the president was unable to function.[30]

When President Dwight D. Eisenhower suffered a heart attack in September 1955, he and Vice President Richard Nixon developed an informal plan authorizing Nixon to assume some administrative duties during Eisenhower's recovery. Although it did not have the force of law, the plan helped to reassure the nation. The agreement also contained a provision whereby Eisenhower could declare his own inability and, if unable to do so, empowered Nixon, with appropriate consultation, to make the decision.[26] Had it been invoked, Nixon would have served as acting president until the president issued a declaration of his recovery. Moved forward as a consequence of President Kennedy's November 1963 assassination, this informal plan evolved into constitutional procedure a decade later through Sections 3 and 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment, which resolved the uncertainties surrounding presidential disability.[11]

Presidential succession by vice presidents

Nine vice presidents have succeeded to the presidency intra-term, eight due to the president's death, and one due to the president's resignation from office.[8][18]

| Successor[31] | Party[31] | President | Reason | Date of succession[31][32] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| John Tyler | Whig | William Henry Harrison | Death | April 4, 1841, 31 days into Harrison's presidency.[33] | |

| Millard Fillmore | Whig | Zachary Taylor | Death | July 9, 1850, 1 year, 4 months and 5 days into Taylor's presidency.[34] | |

| Andrew Johnson | National Union | Abraham Lincoln | Death | April 15, 1865, 1 month and 11 days into Lincoln's 2nd term.[35] | |

| Chester A. Arthur | Republican | James A. Garfield | Death | September 19, 1881, 6 months and 15 days into Garfield's presidency.[36] | |

| Theodore Roosevelt | Republican | William McKinley | Death | September 14, 1901, 6 months and 10 days into McKinley's 2nd term.[37] | |

| Calvin Coolidge | Republican | Warren G. Harding | Death | August 2, 1923, 2 years, 4 months and 29 days into Harding's presidency.[38] | |

| Harry S. Truman | Democratic | Franklin D. Roosevelt | Death | April 12, 1945, 2 months and 23 days into Roosevelt's 4th term.[39] | |

| Lyndon B. Johnson | Democratic | John F. Kennedy | Death | November 22, 1963, 2 years, 10 months and 2 days into Kennedy's presidency.[40] | |

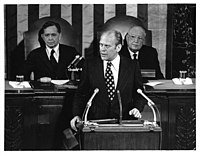

| Gerald Ford | Republican | Richard Nixon | Resignation | August 9, 1974, 1 year, 6 months and 20 days into Nixon's 2nd term.[41] | |

Additionally, three vice presidents have temporarily assumed the powers and duties of the presidency as acting president, as authorized by Section 3 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment: George H. W. Bush did so once, on July 13, 1985; Dick Cheney did so twice, on June 29, 2002 and again on July 21, 2007; and Kamala Harris did so on November 19, 2021.[42][43]

Presidential succession beyond the vice president

While several vice presidents have succeeded to the presidency upon the death or resignation of the president, and a number of them have died or resigned, the offices of president and vice president have never been simultaneously vacant;[H][I] thus no other officer in the presidential line of succession has ever been called upon to act as president. There was potential for such a double vacancy when John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln in 1865, as Vice President Andrew Johnson was also targeted (along with Secretary of State William Seward and possibly General Ulysses S. Grant) as part of Booth's plot to destabilize the Union government.[48] It again became a real possibility three years later, when, with the vice presidency vacant, Johnson as president was impeached by the House of Representatives and faced removal from office if convicted at trial in the Senate. Johnson was acquitted by a one-vote margin.[49]

The 25th Amendment's mechanism for filling vice presidential vacancies has reduced the likelihood that the House speaker, Senate president pro tempore, or any cabinet member will need to serve as acting president.[10] In October 1973, the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew made House Speaker Carl Albert first in line to succeed President Richard Nixon – but only briefly, as Gerald Ford was sworn in as vice president on December 6, 1973.[50] On August 9, 1974, Nixon resigned the presidency, making Ford president; Albert was then again next in line, but only for the four months it took for Nelson Rockefeller to be nominated and confirmed as Ford's vice president.[8]

Next in line

Since 1789 there have been eighteen instances of the vice presidency becoming vacant;[32] during those periods, the persons next in line to serve as acting president were:

Under the 1792 succession act

| No. | Official (party) | Dates | Reason | President (party) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | William H. Crawford (D-R)[51] President pro tempore of the Senate |

April 20, 1812 –

March 4, 1813 |

Death of Vice President George Clinton | Madison (D-R) | ||

| 2 | Langdon Cheves (D-R)[52] Speaker of the House |

November 23, 1814 –

November 25, 1814 |

Death of Vice President Elbridge Gerry, and vacancy in office of president pro tempore of the Senate | Madison (D-R) | ||

| John Gaillard (D-R)[52] President pro tempore of the Senate |

November 25, 1814 –

March 4, 1817 |

John Gaillard elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| 3 | Hugh Lawson White (D)[52] President pro tempore of the Senate |

December 28, 1832 –

March 4, 1833 |

Resignation of Vice President John C. Calhoun | Jackson (D) | ||

| 4 | Samuel L. Southard (W)[53] President pro tempore of the Senate |

April 4, 1841 –

May 31, 1842 |

Death of President William Henry Harrison and accession of Vice President John Tyler to presidency | Tyler (W) | ||

| Willie Person Mangum (W)[53] President pro tempore of the Senate |

May 31, 1842 –

March 4, 1845 |

Willie Person Mangum elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| 5 | Vacant[54]

|

July 9, 1850 –

July 11, 1850 |

Death of President Zachary Taylor and accession of Vice President Millard Fillmore to presidency, vacancy in office of president pro tempore of the Senate, and ineligibility of Speaker of the House Howell Cobb[J] | Fillmore (W) | ||

| William R. King (D)[55] President pro tempore of the Senate |

July 11, 1850 –

December 20, 1852 |

William R. King elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| David Rice Atchison (D)[56] President pro tempore of the Senate |

December 20, 1852 –

March 4, 1853 |

David Rice Atchison elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| 6 | David Rice Atchison (D)[54] President pro tempore of the Senate |

April 18, 1853 –

December 4, 1854 |

Death of Vice President William R. King | Pierce (D) | ||

| Lewis Cass (D)[54] President pro tempore of the Senate |

December 4, 1854 –

December 5, 1854 |

Lewis Cass elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| Jesse D. Bright (D)[54] President pro tempore of the Senate |

December 5, 1854 –

June 9, 1856 |

Jesse D. Bright elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| Charles E. Stuart (D)[54] President pro tempore of the Senate |

June 9, 1856 –

June 10, 1856 |

Charles E. Stuart elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| Jesse D. Bright (D)[54] President pro tempore of the Senate |

June 11, 1856 –

January 6, 1857 |

Jesse D. Bright elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| James Murray Mason (D)[54] President pro tempore of the Senate |

January 6, 1857 –

March 4, 1857 |

James Murray Mason elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| 7 | Lafayette S. Foster (R)[57] President pro tempore of the Senate |

April 15, 1865 –

March 2, 1867 |

Death of President Abraham Lincoln and accession of Vice President Andrew Johnson to presidency | A. Johnson (NU) | ||

| Benjamin Wade (R)[57] President pro tempore of the Senate |

March 2, 1867 –

March 4, 1869 |

Benjamin Wade elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| 8 | Thomas W. Ferry (R)[58] President pro tempore of the Senate |

November 22, 1875 –

March 4, 1877 |

Death of Vice President Henry Wilson | Grant (R) | ||

| 9 | Vacant[59]

|

September 19, 1881 –

October 10, 1881 |

Death of President James A. Garfield and accession of Vice President Chester A. Arthur to presidency, and vacancy in office of president pro tempore of the Senate and in office of speaker of the House | Arthur (R) | ||

| Thomas F. Bayard (D)[60] President pro tempore of the Senate |

October 10, 1881 –

October 13, 1881 |

Thomas E. Bayard elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| David Davis (I)[60] President pro tempore of the Senate |

October 13, 1881 –

March 3, 1883 |

David Davis elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| George F. Edmunds (R)[60] President pro tempore of the Senate |

March 3, 1883 –

March 3, 1885 |

George F. Edmunds elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| 10 | Vacant[59]

|

November 25, 1885 –

December 7, 1885 |

Death of Vice President Thomas A. Hendricks, and vacancy in office of president pro tempore of the Senate and in office of speaker of the House | Cleveland (D) | ||

| John Sherman (R)[59] President pro tempore of the Senate |

December 7, 1885 –

January 19, 1886 |

John Sherman elected president pro tempore of the Senate, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

Under the 1886 succession act

| No. | Official (party) | Dates | Reason | President (party) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Thomas F. Bayard (D)[23] Secretary of State |

January 19, 1886 –

March 4, 1889 |

Succession Act of 1886 is enacted, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | Cleveland (D) | ||

| 11 | John Hay (R)[61] Secretary of State |

November 21, 1899 –

March 4, 1901 |

Death of Vice President Garret Hobart | McKinley (R) | ||

| 12 | John Hay (R)[61] Secretary of State |

September 14, 1901 –

March 4, 1905 |

Death of President William McKinley and accession of Vice President Theodore Roosevelt to presidency | T. Roosevelt (R) | ||

| 13 | Philander C. Knox (R) Secretary of State |

October 30, 1912 –

March 4, 1913 |

Death of Vice President James S. Sherman | Taft (R) | ||

| 14 | Charles Evans Hughes (R) Secretary of State |

August 2, 1923 –

March 4, 1925 |

Death of President Warren G. Harding and accession of Vice President Calvin Coolidge to the presidency | Coolidge (R) | ||

| 15 | Edward Stettinius Jr. (D)[62] Secretary of State |

April 12, 1945 –

June 27, 1945 |

Death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and accession of Vice President Harry S. Truman to the presidency | Truman (D) | ||

| Henry Morgenthau Jr. (D)[62] Secretary of the Treasury |

June 27, 1945 –

July 3, 1945 |

Resignation of Secretary of State Edward Stettinius Jr., and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| James F. Byrnes (D)[62] Secretary of State |

July 3, 1945 –

January 21, 1947 |

James F. Byrnes confirmed as Secretary of State, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| George Marshall (D)[61] Secretary of State |

January 21, 1947 –

July 18, 1947 |

George Marshall confirmed as Secretary of State, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

Under the 1947 succession act

| No. | Official (party) | Dates | Reason | President (party) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | Joseph W. Martin Jr. (R)[61] Speaker of the House |

July 18, 1947 –

January 3, 1949 |

Succession Act of 1947 is enacted, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | Truman (D) | ||

| Sam Rayburn (D)[63] Speaker of the House |

January 3, 1949 –

January 20, 1949 |

Sam Rayburn elected speaker of the House, and continuing intra-term vacancy in vice presidency | ||||

| 16 | John W. McCormack (D)[64] Speaker of the House |

November 22, 1963 –

January 20, 1965 |

Death of President John F. Kennedy and accession of Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson to the presidency | L. Johnson (D) | ||

| 17 | Carl Albert (D)[50] Speaker of the House |

October 10, 1973 –

December 6, 1973 |

Resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew | Nixon (R) | ||

| 18 | Carl Albert (D)[8] Speaker of the House |

August 9, 1974 –

December 19, 1974 |

Resignation of President Richard Nixon and accession of Vice President Gerald Ford to the presidency | Ford (R) | ||

Contemporary issues and concerns

In 2003, the Continuity of Government Commission suggested that the succession law has "at least seven significant issues ... that warrant attention", specifically:

- The reality that all figures in the line of succession work and reside in the vicinity of Washington, D.C. In the event of a disaster such as a nuclear, chemical, or biological attack, it is possible that everyone on the list would be killed or incapacitated. For this concern, one of the listed people is selected as "designated survivor" and stays at an undisclosed secure location during certain events where all others are present, such as the State of the Union address.

- Doubt that the speaker of the House and the president pro tempore of the Senate are constitutionally eligible to act as president.

- A concern about the wisdom of including the president pro tempore in the line of succession as the "largely honorific post traditionally held by the longest-serving senator of the majority party". For example, from January 20, 2001, to June 6, 2001, the president pro tempore was then-98-year-old Strom Thurmond.

- A concern that the line of succession can force the presidency to abruptly switch parties mid-term, as the president, speaker, and the president pro tempore are not necessarily of the same party as each other.

- A concern that the succession line is ordered by the dates of creation of the various executive departments, without regard to the skills or capacities of the persons serving as secretary.

- The fact that, should a Cabinet member begin to act as president, the law allows the House to elect a new speaker (or the Senate to elect a new president pro tempore), who could in effect remove the Cabinet member and assume the office themselves at any time.

- The absence of a provision where a president is disabled and the vice presidency is vacant (for example, if an assassination attempt simultaneously wounded the president and killed the vice president).[65]

In 2009, the Continuity of Government Commission commented on the use of the term "Officer" in the 1947 statute,

The language in the current Presidential Succession Act is less clear than that of the 1886 Act with respect to Senate confirmation. The 1886 Act refers to "such officers as shall have been appointed by the advice and consent of the Senate to the office therein named …" The current act merely refers to "officers appointed, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate." Read literally, this means that the current act allows for acting secretaries to be in the line of succession as long as they are confirmed by the Senate for a post (even for example, the second or third in command within a department). It is common for a second in command to become acting secretary when the secretary leaves office. Though there is some dispute over this provision, the language clearly permits acting secretaries to be placed in the line of succession. (We have spoken to acting secretaries who told us they had been placed in the line of succession.)[66]

In 2016–2017, the Second Fordham University School of Law Clinic on Presidential Succession developed a series of proposals to "resolve succession issues that have received little attention from scholars and commissions" over the past several decades; its recommendations included:

- Removing legislators and several Cabinet members from the line of succession and adding four officials, or "Standing Successors", outside of Washington, D.C. The line of succession would be: 1st—Secretary of State, 2nd—Secretary of Defense, 3rd—Attorney General, 4th—Secretary of Homeland Security, 5th—Secretary of the Treasury, 6th—Standing Successor 1, 7th—Standing Successor 2, 8th—Standing Successor 3, and 9th—Standing Successor 4;

- If legislators are not removed from the line of succession, only designate them as successors in cases where the president dies or resigns, not where he is disabled (to protect legislators from being forced to resign to act as president temporarily) or removed from office;

- Eliminate the "bumping provision" in the Succession Act of 1947;

- Clarify the ambiguity in the Succession Act of 1947 as to whether acting Cabinet secretaries are in the line of succession;

- That the outgoing president nominate and the Senate confirm some of the incoming president's Cabinet secretaries prior to Inauguration Day, which is a particular point of vulnerability for the line of succession;

- Establish statutory procedures for declaring 1) a dual inability of the president and the vice president, including where there is no vice president and 2) a sole inability of the vice president.[67]

See also

- Central Locator System

- Designated survivor

- List of United States presidential assassination attempts and plots

Notes

- ^ a b Eligible if acting officers whose prior executive branch appointment required Senate confirmation are included in the line of succession, which is unclear. The current succession act states that the list of eligible cabinet officers includes only "officers appointed, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate," whereas the previous act stated that the list (of eligible cabinet secretaries) only applied to persons confirmed to "the offices therein named," thus excluded acting secretaries. Many officials who serve as acting secretaries have previously received Senate confirmations for deputy-level posts, and so might be eligible under the more ambiguous wording of the current law.[4]

- ^ a b Ineligible due to being a naturalized citizen, not natural-born.

- ^ The final sentence of the 12th Amendment explicitly states that the constitutional qualifications for holding the presidency also apply to being vice president.[6]

- ^ This section 2 of the 25th Amendment has been invoked twice: 1973—Gerald Ford was nominated and confirmed to office following Spiro Agnew's resignation. 1974—Nelson Rockefeller was nominated and confirmed to office after Ford became president upon Richard Nixon's resignation.[10]

- ^ Secretary of State, Secretary of the Treasury, Secretary of War, Attorney-General, Postmaster-General, Secretary of the Navy, and Secretary of the Interior.

- ^ Secretary of State, Secretary of the Treasury, Secretary of War, Attorney General, Postmaster General, Secretary of the Navy, Secretary of the Interior, Secretary of Agriculture, Secretary of Commerce, Secretary of Labor.

- ^ 1947—substituted Secretary of Defense for Secretary of War and struck out Secretary of the Navy. 1965—added Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare and also Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. 1966—added Secretary of Transportation. 1970—removed Postmaster General. 1977—added Secretary of Energy. 1979—substituted Secretary of Health and Human Services for Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare and added Secretary of Education. 1988—Secretary of Veterans Affairs. 2006—Secretary of Homeland Security.[19]

- ^ Various friends and colleagues of Senator David Rice Atchison asserted that both offices were vacant on March 4–5, 1849, because the terms of President Zachary Taylor and Vice President Millard Fillmore began on March 4, but neither took their oath of office on that day – following precedent as the day fell on a Sunday. The inauguration was held the next day, Monday, March 5.[44] Consequently, they considered David Rice Atchison, by virtue of being the last president pro tempore of the Senate in the out-going Congress, to have been Acting President of the United States during the day-long Interregnum in accordance with the Presidential Succession Act of 1792. Historians, constitutional scholars and biographers all dismiss the claim. Atchison did not take the presidential oath of office either, and his term as president pro tempore had expired on March 4.[45]

- ^ 1940 Republican presidential nominee Wendell Willkie and vice presidential nominee Charles L. McNary both died in 1944 (October 8, and February 25, respectively); the first, and to date only time both members of a major-party presidential ticket died during the term for which they sought election. Had they been elected, Willkie's death would have resulted in the Secretary of State becoming acting president for the remainder of the term ending on January 20, 1945, in accordance with the Presidential Succession Act of 1886.[46][47]

- ^ Not yet 35 years old.

References

- ^ "Title 3—The President: Chapter 1—Presidential Elections and Vacancies" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Publishing Office. 2017. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ "Order of Presidential Succession". USA.gov. US General Services Administration. Archived from the original on November 21, 2024. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

- ^ a b Lord, Debbie (June 18, 2018). "A president resigns, dies or is impeached: What is the line of succession?". WFTV.com. Cox Media Group. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ "The Continuity of the Presidency: The Second Report of the Continuity of Government Commission" (PDF). Preserving Our Institutions. Washington, D.C.: Continuity of Government Commission. June 2009. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 23, 2012 – via WebCite.

- ^ "Article II. The Executive Branch, Annenberg Classroom". The Interactive Constitution. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The National Constitution Center. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Peabody, Bruce G.; Gant, Scott E. (February 1999). "The Twice and Future President: Constitutional Interstices and the Twenty-Second Amendment". Minnesota Law Review. 83 (3). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Law School: 565–635. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c Feerick, John. "Essays on Article II: Presidential Succession". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Feerick, John D. (2011). "Presidential Succession and Inability: Before and After the Twenty-Fifth Amendment". Fordham Law Review. 79 (3): 907–949. Archived from the original on October 11, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Larson, Edward J.; Shesol, Jeff. "The Twentieth Amendment". The Interactive Constitution. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The National Constitution Center. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Neale, Thomas H. (September 27, 2004). "Presidential and Vice Presidential Succession: Overview and Current Legislation" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, the Library of Congress. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Kalt, Brian C.; Pozen, David. "The Twenty-fifth Amendment". The Interactive Constitution. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The National Constitution Center. Archived from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Spivak, Joshua (October 14, 2015). "America's System for Presidential Succession is Ridiculous". Time. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Relyea, Harold C. (August 5, 2005). "Continuity of Government: Current Federal Arrangements and the Future" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, the Library of Congress. pp. 2–4. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c Hamlin, Charles S. (January 1905). "The Presidential Succession Act of 1886". Harvard Law Review. 18 (3). The Harvard Law Review Association: 182–195. doi:10.2307/1323239. JSTOR 1323239. Archived from the original on January 2, 2023. Retrieved March 13, 2021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Feerick, John D.; Freund, Paul A. (1965). From Failing Hands: the Story of Presidential Succession. New York City: Fordham University Press. pp. 57–62. LCCN 65-14917. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ Lewis, Charlton Thomas; Willsey, Joseph H. (1895). Harper's Book of Facts: a Classified History of the World; Embracing Science, Literature, and Art. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 884. LCCN 01020386. Archived from the original on January 2, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ^ Truman, Harry S. (June 19, 1945). "Special Message to the Congress on the Succession to the Presidency". Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "Succession: Presidential and Vice Presidential Fast Facts". CNN.com. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. August 27, 2013. Archived from the original on October 3, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ "2016 US Code Title 3 – The President Chapter 1 – Presidential Elections and Vacancies Sec. 19 – Vacancy in offices of both President and Vice President; officers eligible to act". US Law. Mountain View, California: Justia. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ a b Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. (Autumn 1974). "On the Presidential Succession". Political Science Quarterly. 89 (3): 475, 495–496. doi:10.2307/2148451. JSTOR 2148451.

- ^ a b "Presidential Succession". US Law. Mountain View, California: Justia. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ a b c Freehling, William (October 4, 2016). "John Tyler: Domestic Affairs". Charllotesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on November 26, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Rankin, Robert S. (February 1946). "Presidential Succession in the United States". The Journal of Politics. 8 (1): 44–56. doi:10.2307/2125607. JSTOR 2125607. S2CID 153441210.

- ^ a b c d e Abbott, Philip (December 2005). "Accidental Presidents: Death, Assassination, Resignation, and Democratic Succession". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 35 (4): 627–645. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2005.00269.x. JSTOR 27552721.

- ^ Crapol, Edward P. (2006). John Tyler: the accidental president. UNC Press Books. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8078-3041-3. OCLC 469686610.

- ^ a b Feerick, John. "Essays on Amendment XXV: Presidential Succession". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ a b Feerick, John D.; Freund, Paul A. (1965). From Failing Hands: the Story of Presidential Succession. New York City: Fordham University Press. pp. 118–127. LCCN 65-14917. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ Amber, Saladin (October 4, 2016). "Woodrow Wilson: Life After The Presidency". Charllotesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ "Thomas R. Marshall, 28th Vice President (1913–1921)". Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress 1774 – Present. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress. Archived from the original on March 4, 2023. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ Cooper, John M. (2009). Woodrow Wilson: A Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 555. ISBN 978-0-307-26541-8.

- ^ a b c Neale, Thomas H. (September 27, 2004). "Presidential and Vice Presidential Succession: Overview and Current Legislation" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, the Library of Congress. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b "Vice President of the United States (President of the Senate)". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary, United States Senate. Archived from the original on November 15, 2002. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ Freehling, William (October 4, 2016). "William Harrison: Death of the President". Charllotesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on August 18, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Holt, Michael (October 4, 2016). "Zachary Taylor: Death of the President". Charllotesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Burlingame, Michael (October 4, 2016). "Abraham Lincoln: Death of the President". Charllotesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Freidel, Frank; Sidey, Hugh. "James Garfield". WhiteHouse.gov. From "The Presidents of the United States of America". (2006) Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Freidel, Frank; Sidey, Hugh. "William McKinley". WhiteHouse.gov. From "The Presidents of the United States of America". (2006) Washington D.C.: White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Trani, Eugene P. (October 4, 2016). "Warren G. Harding: Death of the President". Charllotesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Freidel, Frank; Sidey, Hugh. "Franklin D. Roosevelt". WhiteHouse.gov. From "The Presidents of the United States of America". (2006) Washington D.C.: White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on December 19, 2017. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Freidel, Frank; Sidey, Hugh. "John F. Kennedy". WhiteHouse.gov. From "The Presidents of the United States of America". (2006) Washington D.C.: White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on May 5, 2023. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Hughes, Ken (October 4, 2016). "Richard Nixon: Life After the Presidency". Charllotesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Olsen, Jillian (November 19, 2021). "How many other vice presidents have temporarily taken over presidential powers?". St. Petersburg, Florida: WTSP. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Kate (November 19, 2021). "For 85 minutes, Kamala Harris became the first woman with presidential power". CNN. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ "The 16th Presidential Inauguration: Zachary Taylor, March 5, 1849". Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies. Archived from the original on March 4, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ Feerick, John D.; Freund, Paul A. (1965). From Failing Hands: the Story of Presidential Succession. New York City: Fordham University Press. pp. 100–101. LCCN 65-14917. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ Brewer, F. (1945). "Succession to the presidency". Editorial research reports 1945 (Vol. II). Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

If the Republican ticket had been elected in 1940, the plan of succession adopted in 1886 would probably have come into operation for the first time in 1944. Charles McNary, Republican candidate for Vice President, died on Feb. 25, 1944, With the death of Wendell Willkie, on Oct. 8, his Secretary of State would have been sworn in for the remainder of the term ending on Jan. 20, 1945.

- ^ Feinman, Ronald L. (March 1, 2016). "The Election of 1940 and the Might-Have-Been that Makes One Shudder". History News Network. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ^ "Booth's Reason for Assassination". Teachinghistory.org. Fairfax County, Virginia: Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. Archived from the original on January 19, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ "The forgotten man who almost became President after Lincoln". The constitution Daily. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The National Constitution Center. April 15, 2018. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Gup, Ted (November 28, 1982). "Speaker Albert Was Ready to Be President". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 28, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ "George Clinton, 4th Vice President (1805–1812)". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary, United States Senate. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- ^ a b c Feerick, John D.; Freund, Paul A. (1965). From Failing Hands: the Story of Presidential Succession. New York City: Fordham University Press. pp. 84, 86. LCCN 65-14917. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ a b "John Tyler, Tenth Vice President (1841)". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary, United States Senate. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Feerick, John D.; Freund, Paul A. (1965). From Failing Hands: the Story of Presidential Succession. New York City: Fordham University Press. pp. 104–105. LCCN 65-14917. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ "William Rufus King, 13th Vice President (1853)". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary, United States Senate. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- ^ "President Pro Tempore". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary, United States Senate. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Bomboy, Scott (August 11, 2017). "Five little-known men who almost became president". Constitution Daily. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: National Constitution Center. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ Feerick, John D.; Freund, Paul A. (1965). From Failing Hands: the Story of Presidential Succession. New York City: Fordham University Press. p. 116. LCCN 65-14917. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c Erickson, Nancy, ed. (August 22, 2008). "Chapter 2: A Question of Succession, 1861-1889" (PDF). Pro tem : presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate since 1789. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing office. pp. 55–57. ISBN 978-0-16-079984-6. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- ^ a b c Feerick, John D.; Freund, Paul A. (1965). From Failing Hands: the Story of Presidential Succession. New York City: Fordham University Press. pp. 131–132. LCCN 65-14917. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Feinman, Ronald L. (March 22, 2016). "These 11 People Came Close to Being President of the United States …". Seattle, Washington: History News Network. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c Feerick, John D.; Freund, Paul A. (1965). From Failing Hands: the Story of Presidential Succession. New York City: Fordham University Press. pp. 204–205. LCCN 65-14917. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- ^ "List of Speakers of the House". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ Feinman, Ronald L. (November 1, 2015). "Three Speakers Of The House Who Were "A Heartbeat Away" From The Presidency!". TheProgressiveProfessor. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ "The Continuity of Congress: The First Report of the Continuity of Government Commission" (PDF). Preserving Our Institutions. Washington, D.C.: Continuity of Government Commission. May 2003. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2008. Retrieved December 28, 2008 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Continuity of the Presidency: The Second Report of the Continuity of Government Commission" (PDF). Preserving Our Institutions. Washington, D.C.: Continuity of Government Commission. June 2009. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 23, 2012 – via WebCite.

- ^ "Second Fordham University School of Law Clinic on Presidential Succession, Fifty Years After the Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Recommendations for Improving the Presidential Succession System". Fordham Law Review. 86 (3): 917–1025. 2017. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

Further reading

- Baker, M. Miller (December 1, 2001). "Fools, Drunkards, & Presidential Succession". Federalist Society.

- Feerick, John D. (2011). "Presidential Succession and Inability: Before and After the Twenty-Fifth Amendment". Fordham Law Review. 79 (3): 907–949. Also available here.

- Neale, Thomas H. (October 3, 2008). Presidential Succession: Perspectives, Contemporary Analysis, and 110th Congress Proposed Legislation. Congressional Research Service Report for Congress. RL34692.

- Whitney, Gleaves (2004). "Presidential Succession". Ask Gleaves. Paper 57. Grand Valley State University.